Futura Automation is an American company owing a profound debt of gratitude to everyone who has made America the home of liberty and freedom that it is today. As the founder of Futura Automation, I am offering this excerpt from the auto-biography of my father, Donald W McMorris, as an example of and tribute to the men and women who have defended and built America over the past 240+ years. We pick up the story in summer 1950….

….Following junior year [of college at Oregon State College (to be renamed Oregon State University) with participation in the Reserve Officers Training Corp program], Don attended a summer camp at Fort Lewis, Washington. This was a four credit-hour program training with regular US Army troops of the Second Army Division. It was fundamentally similar to Army Basic Training, but more advanced. During that training session, the Korean War broke out and the Second Division immediately shipped out for the combat zone. We cadets were unsure of what would happen to us. The division was short of equipment as well as shorthanded, would we be going with them? Don was successful in this class and completed the studies second highest of the group from Oregon State College. As a result he was promoted to the rank of Cadet Major for the final year of Military Science classes.

Senior year in Pharmacy School during those years was all about professional studies. Seniors wore white coats to class, and most of the work was in prescription practice and compounding. Don also took a class in Manufacturing Pharmacy. He admired the professor, Fred Grill, who had been employed by a pharmaceutical manufacturer and Professor Grill was very generous in giving A’s to Don. Professor Grill did not stay long with Oregon State College, but moved to Portland where he remained an inspiration to practicing pharmacists in that area for many years.

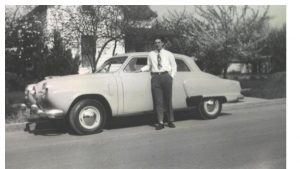

Don’s father would not let him buy a car through his high school and college years, even though Don had the money. Dad correctly said that his son could not afford college, insurance and a car, so Don during his senior college year approached the dealer and ordered a new Studebaker Champion two-door sedan to be delivered on his birthday, April 12th. The new car cost about $1800. And had a six cylinder in-line engine that produced just under 100 horsepower and had a top speed of about 65 miles an hour but got about 30 miles a gallon.

While other classes were taking finals, before graduation, the pharmacy class was preparing for Oregon State Board of Pharmacy examinations. That test took two full days, and covered material from all four years of college. Following completion of internship, the pharmacy intern could take another test that involved working in a Board member store for a day. Complicated prescriptions were saved up to be prepared by the candidate. Don later was advised that he had passed the examinations with the highest grade in the group that took the examination, and was awarded a license to practice pharmacy in Oregon. Don proudly graduated from Oregon State College in June of 1951 with a Bachelors Degree in Pharmacy and a minor in Military Science. He remains a Beaver Believer yet today!

Life in the Military

With graduation a commission in the United States Army Reserves as a Second Lieutenant was awarded. Don recognized that he was most likely to be called into active duty in the army, so he resigned a position he had received at a pharmacy in Cottage Grove as an intern. As expected, orders for extended active duty effective 11 July 1951 were soon received with instructions for vaccinations to be received from a civilian physician and a complete physical to be given at Vancouver Barracks, Washington. Upon completion of two days of physical examinations, Don was ordered to active duty with the 66th Field Artillery Group in Fort Lewis, Washington on 9 September with further instructions to attend the Associate Field Artillery Battery Officers Course at Fort Sill, Oklahoma beginning 19 September.

Don and fellow officer Carl Schmidt left Corvallis in Don’s little Studebaker, taking most of five days to make the trip to Oklahoma. Upon arrival, they were housed in tents because of a shortage of rooms in the Bachelor Officer’s Quarters. They soon began classes in many fields of study including driving tests, and operation of the many vehicles available to the military, of radio and wire communications, survey and other subjects. In the meantime a room in the bachelor officer’s quarters opened when another class completed their course, Don and his friend Carl were able to explore the area on weekends as far as Oklahoma City and to visit his mother’s cousin and her husband.

Other friends arrived at Fort Sill for subsequent classes, including Keith Carpenter from Ontario, Oregon. The most time consuming class was gunnery. Targets were assigned each officer to fire upon and Don had a system of re-plotting each target fired upon by each officer. Officers were given 100 points for each target fired with deductions made for every error. Because he had re-plot data on many targets, Don excelled when it was his turn to fire. His opening rounds fell right on target and his next command was “repeat range and fire for effect”. That gave him a grade of 110, the only grade above 100 in his class, with the extra 10 given for perfect data.

At Christmas time Don was invited to join Keith Carpenter and his wife Kathleen for a trip to her home in Texas. They visited her mother in San Antonio, then drove on south to near the Mexico border and the ranch where Kathleen was raised. Her brother then operated the ranch with cattle as well as growing oranges and onions. One of the days there, Don, Keith and Kathleen set out on horseback to ride the perimeter of the ranch. They rode all day, went back to the house, and then went out the next day to complete the ride.

Returning to Fort Sill, Don and Carl finished the class in February, Don graduating among the top of the group of officers in the class. They decided to drive straight through to Oregon following Route 66, US Highways 99 and 97, crossing the mountains on the Willamette Pass back to 99 and on to Corvallis. The trip took almost exactly 48 hours, and gave them several days at home before continuing on to Fort Lewis.

Don was assigned to Headquarters Battery, 546th Field Artillery Battalion, a 155mm howitzer training unit. He was first assigned as motor officer, then communications officer and finally acted as executive officer, even though outranked by a first lieutenant whom the battery commander did not trust. Don was selected by the battalion commander to teach aircraft loading of heavy equipment such as trucks and cannons, a course he had recently taken at Fort Sill. And he was assigned as safety officer for firing of 105mm howitzers for an overhead artillery course required of soldiers preparing for combat. The Fort Lewis range is too short to fire the 155s, and some years earlier the 105s had knocked down a radio transmission tower in a nearby community.

He also prepared for combat by undergoing overhead fire on a 100 yard course, crawling through barbed wire with live machine gun fire overhead and explosive charges going off nearby. This was accomplished twice, once in daylight and once at night. Other training included combat in cities and villages, entering a chamber filled with tear gas to demonstrate the use of a gas mask, throwing a live grenade and qualifying with the personal weapon, a 45 pistol.

The battalion moved in early April to the Yakima Firing Range to prepare for battalion tests with Don at the rear of the convoy, in radio contact with the battery commander at the head of the column. The first business was to determine the best officer to observe fire for the battalion tests. All junior officers were assembled to fire problems and to be graded by the battalion commander and operations officer. The terrain is difficult – big country with canyons between the observer and target – but Don fired a perfect mission and was chosen to be forward observer for the tests.

In the meantime, Don had received orders dated 2 April to report to Fort Lawton in Seattle on May 13 for transfer to the Far East Command in Yokohama, Japan. The battalion commander advised him that he would not be able to take leave until after battalion tests were completed. The appointed day for the tests arrived and Don as battery executive officer led the battery into the field, then as forward observer, was permitted to return to the barracks until the next morning. He picked up his reconnaissance sergeant and driver and deployed to the “front lines”.

He and the enlisted men dug foxholes and prepared to observe the target area which he had the opportunity to fly over with the battalion pilot a few days earlier. He was assigned a target to fire upon with impact fuses. Then one with time fuses to obtain an air burst. Both missions were successful and Don was permitted to return to base, pack and leave for a few days at home before traveling to Fort Lawton. He took his loyal Studebaker to the dealer and said he would trade it for a new car when he returned from overseas, and asked the dealer to send him a catalog when the new models came out.

Don was deployed to Fort Lawton, Washington in Seattle to prepare for overseas shipment. Some classes were offered, such as ”What to do if you are captured”, but most of the time was free to do what we wished. Usually a group of officers would go downtown for dinner, rather than eat in the mess hall. After about a week we were ordered to Navy Pier to board a troop ship bound for Japan. Don had barely settled into a stateroom when a loudspeaker called his name, along with perhaps forty others to report to the duty officer.

The group was ordered to de-board immediately and report to SeaTac Airport for further orders. Upon arrival, we were advised to repack our duffle bags to a maximum of 25 pounds. Other belongings would be stored at Fort Lewis to await our return stateside. We were to board a charter flight operated by Northwest Airlines and fly directly to Japan to receive further orders. This was NOT good news! Somebody apparently needed us desperately. We flew to Anchorage, Alaska to refuel and get a new flight staff, then to Shemya Island, again to eat, refuel and get another flight staff. We finally arrived at Haneda Airport in Japan and transferred to our billets for the night.

The next day new orders directed most of us to Yokohama and the troop ship “General Howzie” which would carry us to Inchon harbor.

At Inchon we transferred to deuce and a half trucks and were transported to Seoul, where we were billeted overnight and received new orders. Don was ordered to travel by rail to the Replacement Depot in Chun Chon. The train traveled at about 15 miles an hour, and was sidelined to permit freight trains to pass. This short trip took most of the day, and replacements spent the night there to receive new orders. Don was ordered to the 40th Infantry Division, a California National Guard division which had been in Korea for about five months, and the troops were being rotated home. The personnel officer at 40th Division Headquarters, after looking at his file and noting that Don was a pharmacist, first offered him a position as battalion surgeon with a front line infantry battalion. Considering his meager first aid training, Don rejected that offer and asked to be assigned to the artillery. He was ordered and transported by jeep to the 980th Field Artillery Battalion, which was supplied with 105 mm Howitzers and was in support of an infantry regiment.

The commander was Lieutenant Colonel Octavius C. Davis, a gentleman in his late 50’s who had been a career officer and served in the Pacific in World War II, retired and recalled for service in the Korean War. Col. Davis interviewed Don upon his arrival, and asked what his previous assignments had been. Don replied that he had served as headquarters battery executive officer but had received the second highest grade in his gunnery class at Battery Officer School and had been selected to fire the battalion test following a competition between all the junior officers in the battalion at his last assignment. He said that he was a competent forward observer and expected, as the most junior officer in the battalion, to be assigned as a forward observer. The colonel said that was good, because his policy was to assign new replacements who had not seen combat experience as forward observers or liaison officers on the front lines, and it just happened that the last new replacement had just been wounded and sent back to the MASH for rehabilitation.

Don was assigned to B Battery and soon was directed to the front lines as artillery observer for E Company. A driver took Don forward, pointed to a trail that led straight up a hill to the front lines some 200 yards or so distant and asked if the lieutenant would be willing to carry a five gallon can of water, as well as his duffel bag up the hill. Arriving at the top of the hill, Don found a trench line and keeping low, followed it to the observation post. His crew, all new replacements and all buck privates, welcomed him. He set about making a schedule for night observers, teaching them to fire, and chose the best of the lot for chief of section, setting a schedule for promotion of his assistants, assigned one as radio operator and the third as driver. Most of the firing was routine targeting; snipers, mortars and an occasional artillery piece which the enemy would fire a few rounds, then pull back into a cave.

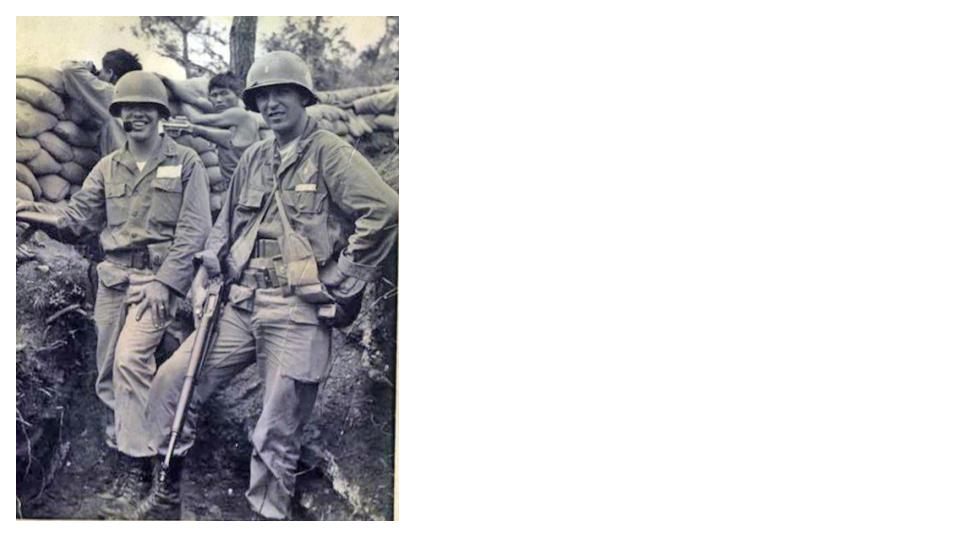

Don (on the right in the photo) accompanied the infantry company commander on one patrol in front of the front lines, visited Lieutenant Donald Koepfler the forward observer with the company to his right and became comfortable with his duties.

[The wounded officer Don replaced] Lieutenant Cliff Houchin returned to the battery following his discharge from the hospital to pick up his belongings and advise the staff that he was appointed aide to the 40th Division Artillery Commanding General. On another occasion he showed up at his old observation post with the general in tow. The general wished to see what the front lines were like, before he rotated home. The E company OP was the only one Cliff was familiar with, as he had spent such little time as an observer. Don led the general to the bunker where a small window permitted a view of the front lines and a mounted telescope brought the enemy trenches into focus. The general couldn’t see well enough so Don led the way to a trench with an open view. General still couldn’t see well enough, so he climbed onto the parapet with his star shining brightly in the sun. The first 122 round [fired at the general by the Chinese] brought the general off the parapet and sent him down the hill to the road. By the time he reached his Jeep, the enemy gunner had found the range and dropped a round right in the trench. Lieutenant Houchin called back on the radio to see if anyone was hit, but Don had retreated to cover and was just shaken up.

After three weeks or so, the 40th division was pulled off line into reserves and replaced by the South Korean Second Division (ROK). The artillery remained on line, because the ROK Second Division had not yet trained their artillery creating a new problem of different customs and an unfamiliar language. It also made many more problems as the bearers who carried their supplies tended to cut the telephone lines and use them to tie the bundles to their backs. The Korean regimental commander solved that problem by making an example of one of the bearers, tied him to the back of a jeep with his purloined wire and dragged him down the road. South Korean patrols tended to go deep into no-mans land, restricting our artillery fire. We told their commanders that it wasn’t possible for a patrol go so far into enemy territory but he insisted that they did indeed go there and to prove it, he had them return with scalps [from Chinese and North Korean soldiers]. Our KMAG advisors [Korean-speaking military advisers] informed the ROK officers that this is not acceptable. Many of the ROK senior officers were trained by the Japanese and followed their methods for discipline.

With time to spare, Don sent a letter to the commander of the Artillery School at Fort Sill, requesting permission to take correspondence courses for the Advanced Field Artillery Battery Officer. This was approved by Fort Sill and forwarded to the battalion commander for approval. About the middle of August, Don received a call from battalion headquarters asking if he would be willing to become Reconnaissance and Survey officer for the battalion. Don was delighted to accept this assignment, and moved his personal belongings to the officer’s quarters at headquarters battery. An additional duty would be to serve as firing officer from midnight to 6:00 AM in rotation with other staff officers.

About this time Don discovered that his ROTC instructor, Colonel Mossberger was a Corps operations officer and Don was able to talk with him on the telephone. Later in August, he, and a Lieutenant Hankins, whom he had met at Fort Sill and who now served with the Seventh Division, were directed by Corps to prepare lesson plans for a five day course to train enlisted personnel in survey methods. The two officers met with over twenty enlisted persons newly arrived in the sector and taught survey procedures and calculations.. Back at battalion headquarters, Colonel Davis advised his staff that each of the nine forward observers should receive a visit from a staff member every month, so they would continue to feel that they were not forgotten on the front lines. Don had the opportunity to make most of those visits, and became thoroughly familiar with the entire regimental front. The rest of the National Guard had rotated home by early September, leaving Assistant Operations Officer Lieutenant Kline to direct the firing center so he was promoted to Operations Officer and Don was directed to take on Assistant Operations Officer duties, as well as Recon and Survey.

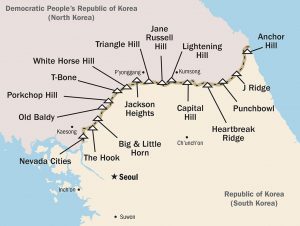

A major and a captain usually filled the positions of Operations Officer and his assistant respectively. Don also discovered that the battalion was involved in planning for a secret operation named “Showdown”, an attack on Triangle Hill directly north of the 32nd Regiment of the Second ROK Division, the regiment which the 980th. was then supporting.

Success in this venture would open a route along the Kumhwa River straight north to the ocean. The plans went through Division to Corps to 8th Army and to the Pentagon and was revised to stop the advance after securing the Triangle Hill complex which included hills Sandy and Jane Russell. Colonel Davis, the battalion commander, wanted to be prepared for any eventuality so he took Don on a reconnaissance to locate battery positions at other locations, one in front of the front lines, and three locations to the rear in case retreat was required. The colonel then directed Don to survey in each location and mark it. The attack began October 14thand became the fifth deadliest battle of the Korean War with American losses of 1539 men killed and wounded. (See the official US Army narrative of this important battle in the Korean War).

Lieutenant Kline and Don both worked 70 hours straight through during the first days of the attack, and both were nominated for the Bronze Star, but neither received the award. Don relates that the night after the attack began Lieutenant Richard Stockton, forward observer with the commander of the ROK 32nd Regiment, found himself and his radio operator were alone on the battlefield. The regimental commander and his troops had withdrawn. Richard called Don on the radio and asked for help. Don told him to find shell craters to get down into, and then the battalion began walking a barrage [of artillery fire] back toward the lieutenant. When it got close, fire was held a few moments while the two men retreated a few yards, and then again began firing in front of the men until they were able to return to the line of South Korean troops they were supporting.

The battalion fired over 10,000 rounds that night from our 18 howitzers, and ammunition trucks were driving to Chun Chon, unloading ammunition directly from aircraft into their trucks and returning with it to our firing batteries. We were at times down to our last few rounds including white phosphorus and chemical shells. The 40th Division was called back to the front, and the 980th Battalion rejoined them in a sector to the northeast near the ocean. Don was promoted to First Lieutenant and Lieutenant Kline was promoted to Captain following this action.

Much of the remainder of the time in Korea was routine duty. December 1, 1952 Don was ordered to Kyoto, Japan for five days Rest and Recuperation leave. He visited the emperor’s summer palace and many other places, one day hiring a taxi which took him and another officer, along with a desk clerk from the hotel, to many other interesting sites that were off the tourist routes. The R & R was extended a couple of days because General Eisenhower, who had just been elected president, flew to Korea to review the situation, and all aircraft were grounded in order to protect him. Returning to the battalion Don and the troops suffered through the bitter cold of winter, saw Christmas and New Years Day pass, and warfare continued at a slightly reduced pace.

Although duties became more routine, there were several challenges which had to be faced. Don continued an informal assignment as Assistant S-3 with two short tours as a battalion and as a regimental liaison officer while other officers went on R & R leave. Another interesting challenge arose when Don was selected to be part of a Corps inspection team to determine if a South Korean infantry division was combat ready. The division was already on line (American units are tested for combat readiness PRIOR to frontline assignment). Don was to inspect an infantry battalion and he decided to inspect each soldier’s weapon, determine that he was supplied with ammunition, and knew how to load and fire the weapon. There are perhaps 300 soldiers in a battalion, so not much time was spent on each. When the front line was inspected, Don told the commander that he would next inspect the outpost, which was almost 2000 yards in front of the front lines. The Korean Colonel said that was much too dangerous and he could not permit it. Don insisted that his general required the inspection and it must go forward. The colonel replied “You don’t understand. If you are killed, then I will be killed by MY general.” The colonel finally agreed to permit the inspection, and Don could go along with a group of bearers who would supply the outpost after dark, but Don would have to return to the front lines alone before daylight and report to him immediately upon return. That task was completed and the report made to Corps and Don returned to his battalion.

The colonel became aware that some of our howitzers were no longer firing in a pattern, probably due to the very rapid firing during the battle for Triangle hill. We had noticed that our tubes were glowing red in the night during that time. Colonel Davis tried to obtain new cannons, but was denied, so he decided to try to calibrate the weapons. He directed Don and Lieutenant James Brinkman, who replaced Don as survey officer, to take care of that task. It would entail surveying in two mountain tops, both of which could view two observation posts in order to accurately locate the two posts by triangulation. Then it would be necessary to locate an appropriate target that could be seen from both posts and fire six to ten rounds from each of 18 howitzers accurately locating the impact of each round by survey techniques.

Don protested that this project would require an extended amount of observation, would be rather dangerous, and that both Jim and Don were due to return stateside in the near future. Perhaps a couple of the new replacements would appreciate the experience. Colonel Davis responded that the two officers named were the most qualified to do the task. There was no other way! The survey was completed, the rounds fired and computations made for each cannon without mishap.

A final challenge arose when a new Korean division requested corps to supply logs to construct battlements. The Koreans had no trucks and the artillery has many of them so a dozen or so trucks were assembled and Don was directed to lead them to a logging operation, have the trucks loaded, then lead them to the Korean division on the front lines. When the trucks arrived at the trail which led up the hill to the front lines the trucks were deployed along the road while Don went up to discuss the operation with the South Korean officer in charge. The Korean wanted all the trucks brought up the hill, but Don insisted that for safety and security only one at a time would approach, unload, and return to their battalion. Of course this took considerable time, but it prevented an artillery barrage taking out all the trucks at once. The project was safely completed and the last truck back home by dark.

Colonel Davis was rotated home in April. Before he left, he called Don in for a conference. He urged Don to consider a career in the military, and said that he had arranged for Don to be named Division Artillery Headquarters Battery Commander. The position would be good for his career, giving him the opportunity to command. Don respectfully rejected the idea of continued service in the Army, and responded that he was looking forward to returning to civilian life as a pharmacist. He recognized the honor of being suggested for a division level position, but he really preferred to remain with the battalion for the remainder of his time in Korea. Col. Davis accepted that, and appointed Don instead as battalion intelligence officer (S-2), which required an FBI security clearance.

The security clearance included interviews with high school and college instructors as well as his father’s employer and Don’s former employer Vin Hurley at the drug store [in Albany, Oregon]. Before he rotated back to the United States Col. Davis wished to inspect the battalion, and asked Don to accompany him. The colonel visited each member of the battalion in their quarters, and took a few minutes to talk with them. One private, when visited, was in his best fatigues and proudly showed his weapon and ammunition, both in a highly polished state. Col. Davis asked, “what do you do with the rest of your ammunition clips?” and the man turning red with embarrassment reached up into the log rafters and pulled out several very dirty clips and handed them to the colonel. The colonel said “very good, I am glad you keep them handy in case you need them.”

A short time later, a new lieutenant colonel arrived to command the battalion as well as a major who would become the S-3. Don was relieved of duties as firing officer and a search was begun for another officer to take his place as S-2. This of course required another FBI review and the first officer chosen failed the FBI check and was even visited by the CID to determine if he was indeed loyal to the United States. This delayed Don’s return stateside some because another officer had to be checked by the FBI. In the meantime, Don was ordered to serve as defense counsel for several court-martials, including one for manslaughter. This was an interesting diversion and Don visited with lawyers from division headquarters for advice on how to handle these cases. Eventually Lieutenant Emmert Hanlin was found by the FBI to be acceptable, and Don signed over all classified documents to him, receiving orders on June 4, 1953 to report to the Inchon Replacement Depot for reassignment. Don left Korea on June 8 aboard the “General Howzie” troop ship bound for home.

The troop ship made a speedy crossing in rough weather, and Don was a compartment commander. He was glad to be an officer as he checked on his crowded compartment filled with seasick enlisted men. The officers had smaller staterooms, four or six to a room and ate at officer’s mess with comfortable captains chairs, stewards and great food served on china plates! The enlisted men ate standing up at long high tables – if they could eat. The troop ship arrived in Seattle harbor in the late afternoon – too late to dock, so the ship was anchored overnight with the city lights so near, but so far across the water. The next morning the ship was docked, officers and men were transported by bus to Fort Lewis, where they were to be reassigned. It was late Friday afternoon before they were settled in quarters at Fort Lewis, so with the weekend ahead, Don called home, got a ride back into Seattle and took a train to Albany, Oregon. His parents and sister Joan met him at the train and he was shortly back home in Corvallis! There was a new Studebaker Hawk waiting for him on Saturday, which had been ordered for him in February. Early Monday morning he drove his new car to Fort Lewis where he was to be separated from the service. The separation process took a few days of physical exams, dental care, and processing of many papers and finally back home. Don was released from active duty July 1, 1953 and reassigned to the reserves.

Recent Comments